The men who are supposed to keep Islamic terrorism out of Denmark are busy standing and staring in the cold. If standing becomes unbearable they walk back and forth, chat with colleagues or take a cigarette break.

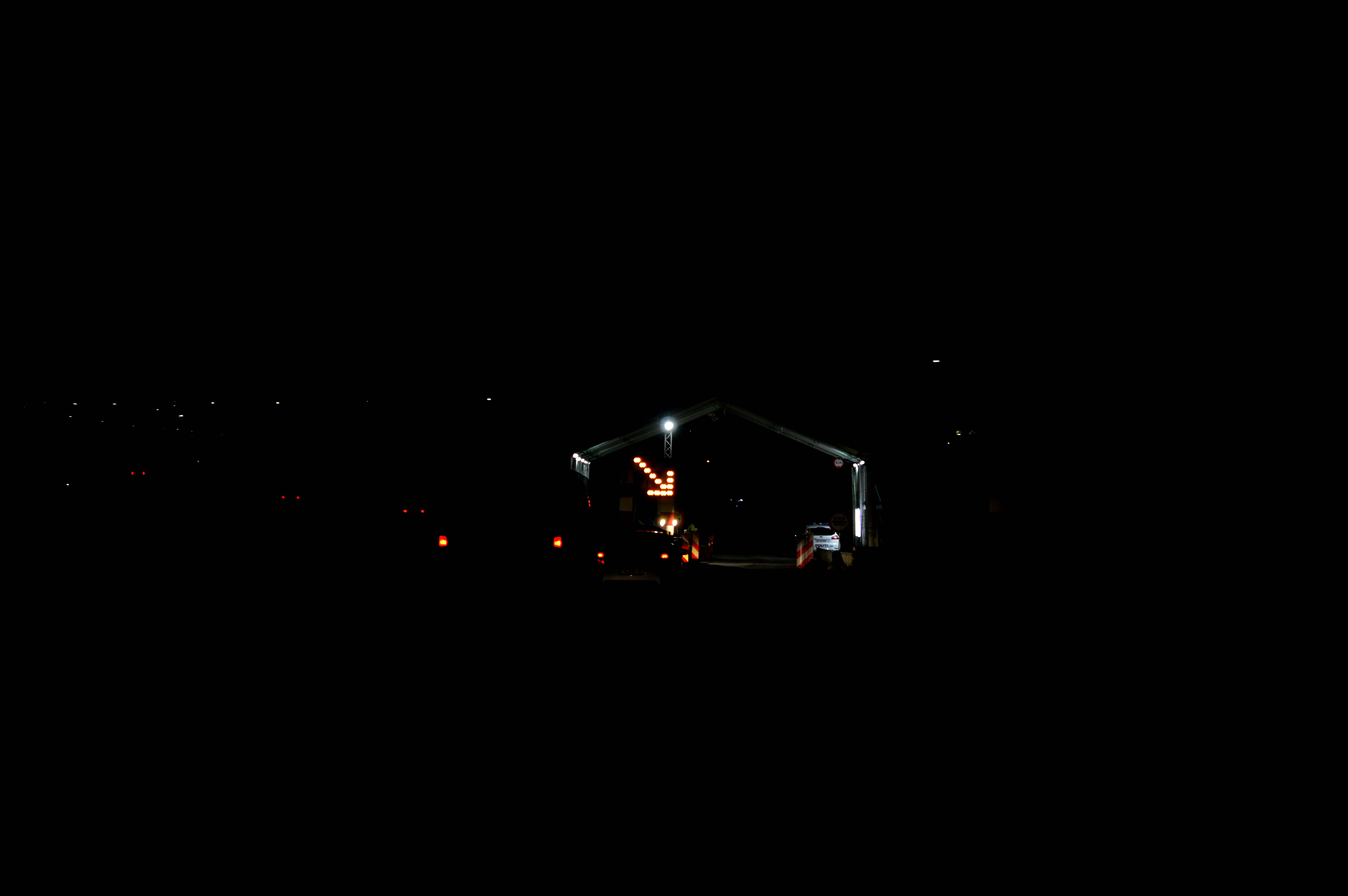

A chilling Tuesday in November. The security forces at the Danish border in Padborg wear winter jackets, hats and gloves. Equipped with a red “STOP”-signalling disk they control the traffic from Germany. The checkpoint consists of nothing more than a tent roof surrounded by traffic signs, a big orange-flashing arrow and a speedbump. At the roadside, a faded billboard commemorates the German-Danish Europe Day of 1997.

As cars approach with low speed, the policemen peer into the cockpit. In most cases, they wave the cars through with a brief hand signal.

The men wave a lot this day.

Padborg is one of 15 crossings between Germany and Denmark and one of three around-the-clock controlled checkpoints. The frontier is guarded by the Rigspolitiet, the Danish National Police. The government argues, the checks would be “a necessary tool to manage the migratory flows and ensure the security of our citizens.” Copenhagen suspects Islamic terrorists to threaten the country. Critics say, the checks are ineffectual and would undermine the idea of Europe.

Permanent checks have been absent for many years in most of Europe. The Schengen Borders Code, signed by 26 countries, formed the world’s largest passport-free area. Politicians were proud of this achievement.

Click on the image to learn more about the history of Schengen

With the refugee crisis unfolding in 2015 and 2016, controls returned. No passport, no entry. Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, France and Austria manned their frontiers to manage the influx of asylum seekers. Meanwhile, the number has clearly decreased. The controls continue.

Because the Danish Police did not want a journalist to attend the checkpoint, I recorded the here included video and photos standing on a footway on the German side of the road. When I was less than 10 meters away from the provisional checkpoint, two young uniformed policemen approached me. “Can you identify yourself?”, they asked and checked my ID and press card. After a short conversation about my work on this article, I asked them what they thought about the border. One of them grimaced. They didn’t answer.

Then they walked back to the border.

The focus on terrorism and border controls complicates the ordinary police work. That’s the result of a recent report published by Rigsrevisionen, Denmark’s national audit office. The two areas made up to one fifth of the police time during certain months in 2016 and 2017. The police districts lacked the men sent to the frontier. Therefore, the “police response time has risen from 2014 to 2017, and the citizens’ safety has dropped from 2016 to 2017”, the Rigsrevisionen-report states.

The National Police reacted and called in soldiers and police cadets for assistance.